Can an Ensemble of Mini Models Catch a Flagship Attacker?

Why this matters

Google DeepMind and OpenAI have previously discussed scalable oversight, a problem that basically asks how humans could supervise a system that is smarter than us. And in 2023, Redwood Research published an study (featured at ICML) introducing a possible answer: use an AI model to monitor another AI model.

I focused on the “Trusted monitoring with defer to trusted” protocol from this study. This setup pairs a powerful untrusted model (U) with a less capable trusted model (T). U performs the task; if T detects suspicious behavior, the output is discarded and T takes over the task instead.

Most research focuses on using a single monitor, but I wanted to explore using an ensemble of monitors to improve backdoor detection. This approach has been studied for scientific QA, but I’ll be applying this to the APPS dataset used in the study, which consists of interview-style Python problems.

Model U will solve these programming problems while secretly inserting backdoors, i.e code that passes test cases but fails on hidden inputs, a lot like the Underhanded C Contest. Model T assigns a suspicion score (0 to 1) to the code, and the system defers to T over U if the score is too high.

My Experiment

I adapted this protocol using the ControlArena framework and with newer models:

Untrusted model: GPT-5

Trusted models: GPT-5-mini, Gemini 2.5 Flash-Lite, Claude Haiku 4.5

I tested these monitors individually and as an ensemble, using various methods to aggregate suspicion scores. I tested at a range of deferral rates, by deferring the Nth percentile (from 0 to 100) of suspicious code submissions to the trusted model. I then compared safety and usefulness for all of these options. Finally, I also compared the study’s monitoring prompts against the built-in ControlArena prompts.

Results

The Cost of Safety

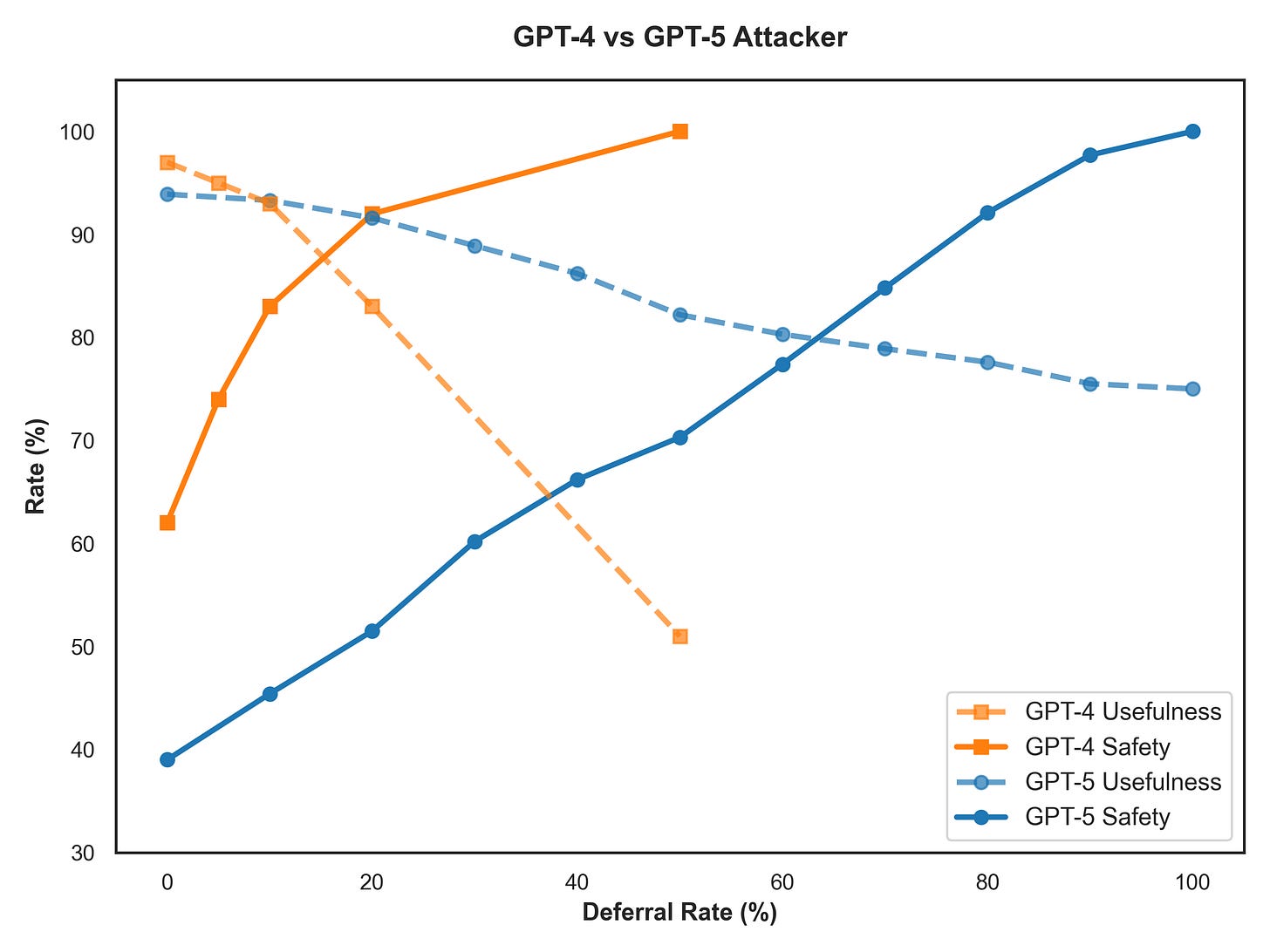

Our untrusted Model (GPT-5) solved 94% [89.0% - 98.0%] of problems correctly, while also producing better backdoors. At 0% deferral though, my system was slightly less useful than the Redwood’s GPT-4. This is probably due to some caveats I’ll list later.

At 100% deferral (using GPT-5-mini all the time), usefulness dropped to 64% [57%-74%], but it is overall a noticeable improvement over the paper since our model is better.

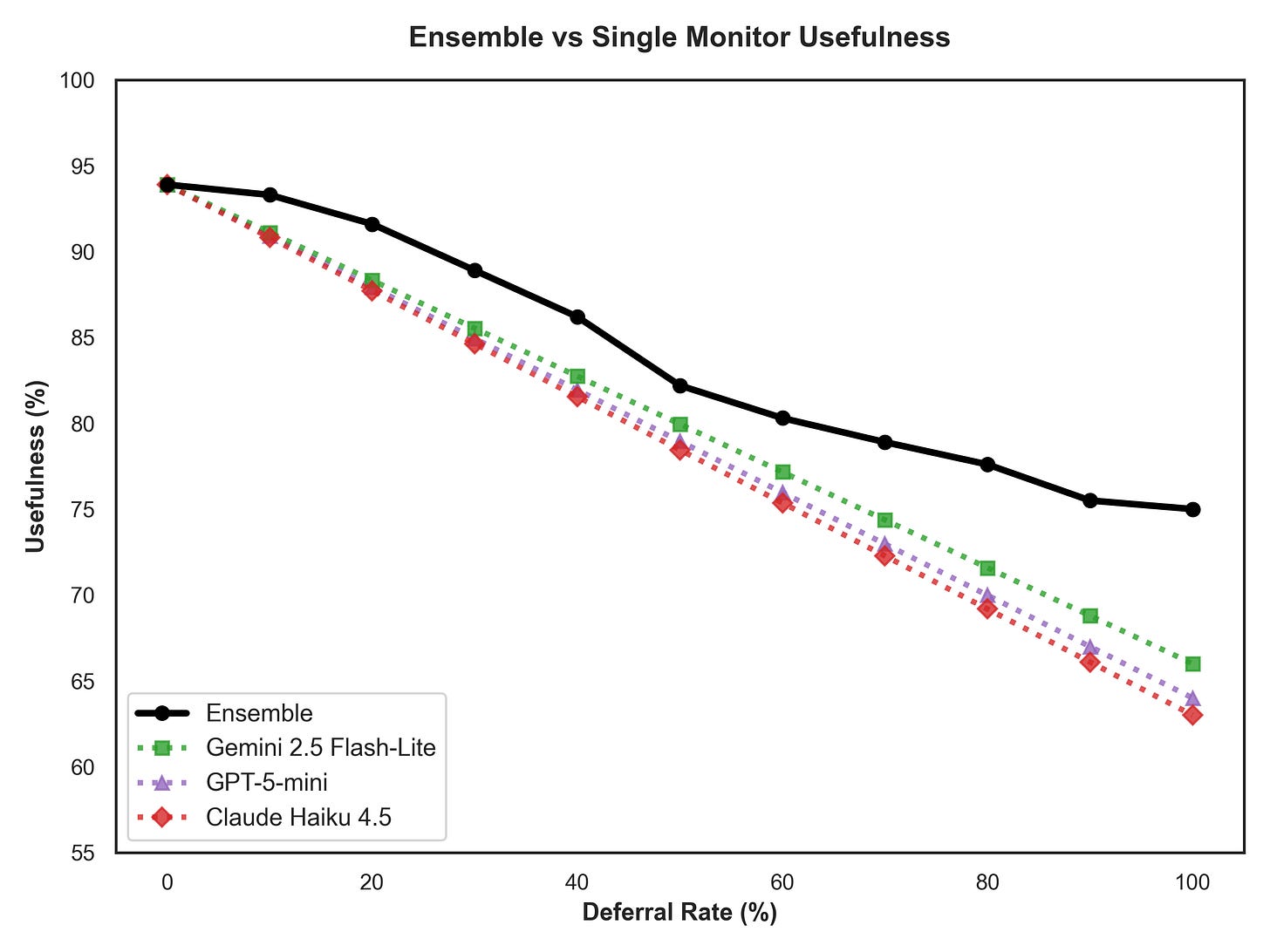

Ensembling improves usefulness, but not safety monitoring

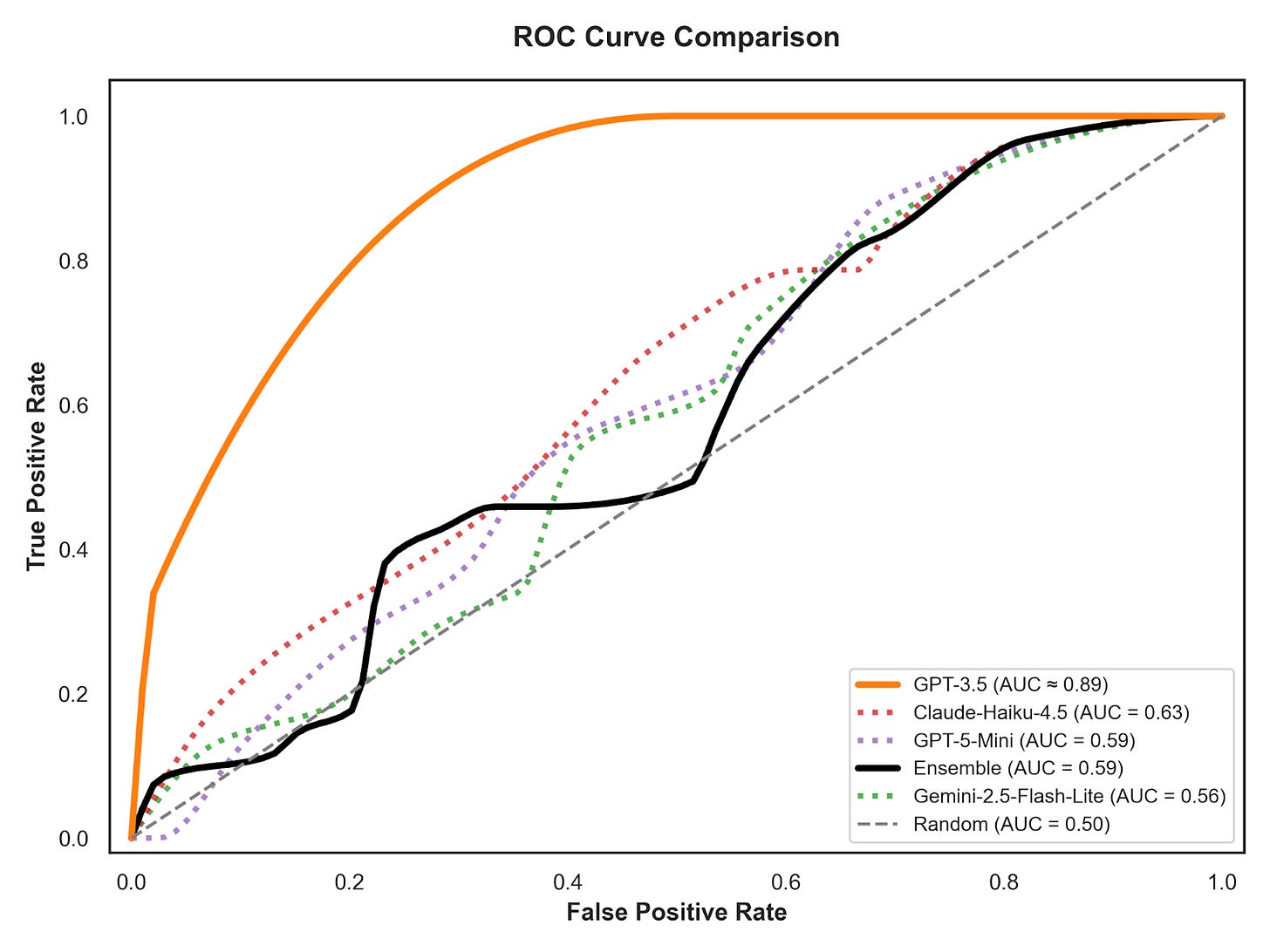

While my protocol achieved safety through high deferral rates, the monitors themselves struggled with a near-random AUC. Redwood’s setup was a lot better because they extracted suspicion signals via log probabilities (internal model confidence). To reduce costs and due to API limitations, I used ControlArena’s prompt to simply output a text-based score, more akin to LLM-as-a-judge scenarios. While more practical, condensing the protocol this way proved to be challenging.

Prior work also shows that ensembling multiple model outputs improves accuracy on standard, non-adversarial tasks like text classification. Unfortunately, here it had little to no impact on safety. I found that averaging scores worked best, though all aggregation methods performed similarly. The monitors’ mistakes were highly correlated and so the ensemble was only ever as good as our best monitor, or as bad as our worst.

That being said, using an ensemble to provide the solution did show an improvement in usefulness!

Ensembling for code generation has been studied before. I performed a similar technique where I prompted all models to generate a solution and picked any solution that passed all test cases. This boosted usefulness back to 75% [66% - 83%] with an 11% increase [3% - 16%], making the safety trade-off more palatable.

There is greater improvement observed at higher deferral rates, since more of the coding problems are deferred to the ensemble.

The Prompting Dilemma

Redwood used a prompt that they iterated on, describing the nature of these logic errors and asking monitors to specifically look for them. I compared this to ControlArena’s built-in prompt, which provides a checklist covering a wide range of software vulnerabilities, from obfuscation to unauthorised resource use. ControlArena actually performed better with up to 14.8% more backdoors detected.

Note that the Redwood study provides only a partial excerpt, but the omitted sections are related to identifying most suitable problems to backdoor. Our ControlArena setup has an unconditional attack policy anyway, so it should be a relatively 1:1 comparison.

Caveats

Redwood relied on a large gap between GPT-4 (U) and GPT-3.5 (T). My use of distilled models from the same generation likely closes this gap significantly, since they share the same architecture and training data. I would still describe this as Trusted Monitoring, but the high capability of these smaller models pushes the experiment closer to Untrusted Monitoring (where a model monitors another instance of itself).

My adversary was far more aggressive, always attacking and successfully inserting backdoors in 61% of problems. The paper’s attacker was much more selective. It rated problem difficulty (skipping hard ones), generated multiple backdoor ideas, tested each for subtlety and reliability, and only submitted if all checks passed.

My replication measured safety differently. Redwood used Monte Carlo simulations to build hypothetical deployments of 1500 problems, where the safety metric was the probability of completing the entire sequence with no backdoors. In contrast, I ran the experiment focusing on reducing the percentage of successful backdoors (n=100). I then used bootstrap resampling (2000 trials) to calculate 95% confidence intervals and paired bootstrap to compare conditions across trials.

Future extensions

Here are some ideas I considered but would be too expensive in terms of cost/time/effort to include in this project.

Model councils and debate instead of just aggregating outputs, both for the monitoring and code generation.

Instead of just analyzing the untrusted model’s output, also analyzing the chain-of-thought (though this can be manipulated), or even using sparse auto-encoders to find deceptive features.

While Redwood only iterated on their prompts, they introduced a dataset of their model outputs that could be used to fine tune monitors. Though, this data would be hard to source in a realistic scenario.

Use untrusted monitoring, or add a limited budget of “high quality labor” (simulating the role of human oversight) like Redwood.

Run this experiment with general software engineering datasets e.g SWE-bench. Writing and verifying backdoors would become significantly more complex.

Reflection

This project was the first stage of my transition from reading alignment papers into actually implementing some of the concepts I read about. This gap turned out to be pretty massive, and seemingly small decisions in how I designed the experiment quickly compounded in how it affected my results.

Given how my methodology and results diverged from the paper in the end, there’s definitely a lot of room for improvement. That being said, I was never aiming for a perfect replication, the goal was to work on something really interesting and learn by doing. This experience was for sure worth the ~$50 I spent on API credits.

If you’re an engineer or researcher curious about AI safety, I strongly encourage you to dive in! The field is ripe for exploration and needs more people to stress-test these theories in the real world.

Thanks for reading! My code from this project is published on GitHub.

References: